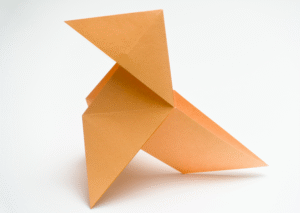

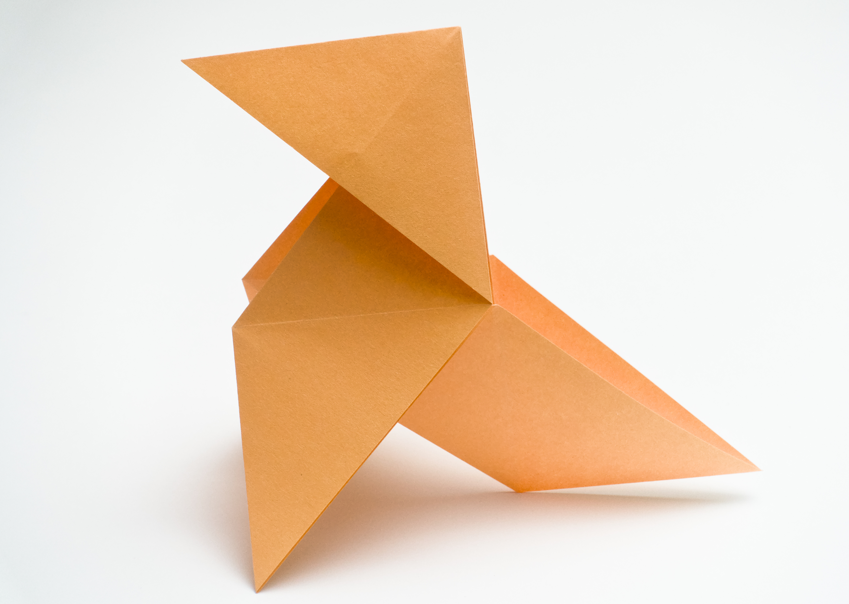

Origami, the art of paper folding, is a practice that blends creativity, precision, and tradition. Though often associated with Japanese culture, the roots of origami stretch across continents and centuries, reflecting a global evolution of paper and its use in artistic expression. From ceremonial beginnings to modern mathematical applications, the history of origami is as intricate as the folds themselves.

The Birth of Paper and Early Folding Traditions

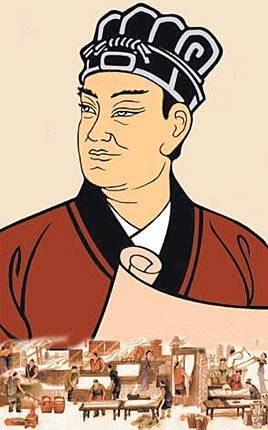

To understand origami, one must first understand the history of paper. Paper was invented in China around 105 CE by Cai Lun, a court official during the Han Dynasty. Early Chinese paper was used for wrapping precious items and in religious ceremonies. While there’s little direct evidence of origami-like practices in ancient China, there is some documentation of folded paper being used in ritual contexts, such as burning paper objects to accompany the deceased in the afterlife.

Paper made its way to Japan via Korea in the 6th century, likely introduced by Buddhist monks. In Japan, paper (known as “kami”) was initially a luxury item used for religious and ceremonial purposes. Over time, Japanese culture developed a reverence for the material, and with it came the practice of paper folding.

Early Japanese Origami: Ritual and Symbolism

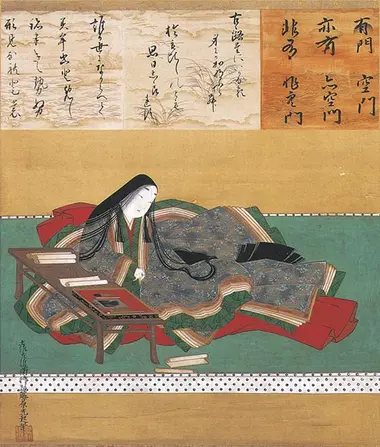

The earliest known form of Japanese paper folding is called origata, which emerged during the Heian period (794–1185). Origata was a ceremonial way of wrapping gifts, with each fold symbolizing a specific intention or form of respect. These folded shapes were not merely decorative—they communicated social and religious messages.

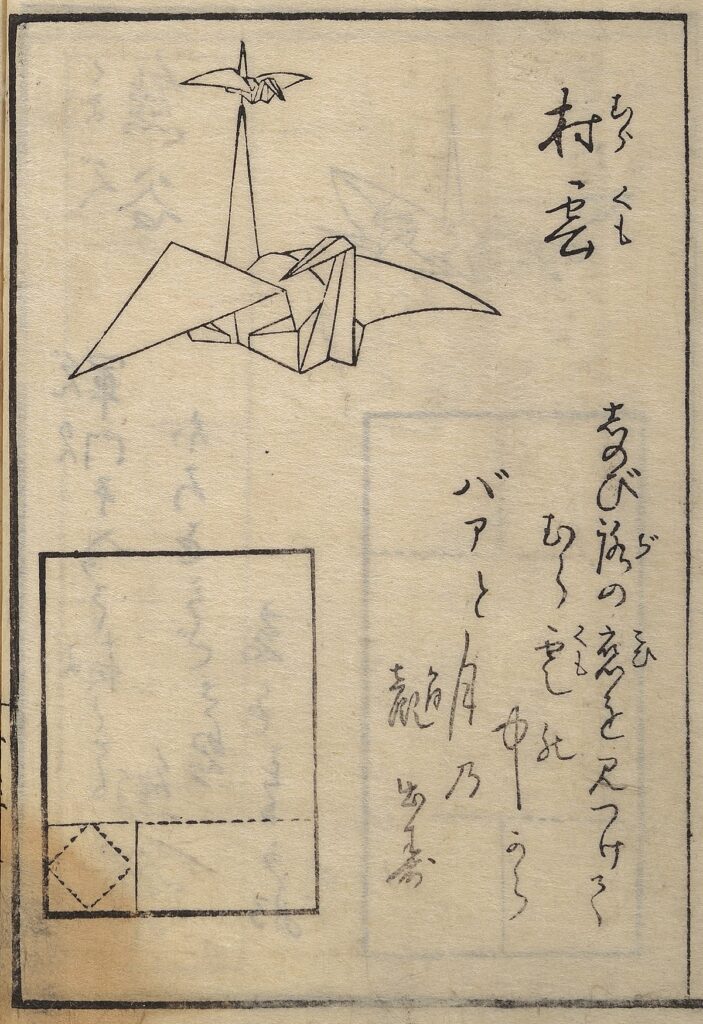

One of the oldest surviving written references to paper folding is found in the 17th-century Japanese work Senbazuru Orikata (How to Fold One Thousand Cranes), published in 1797. This booklet included instructions for folding the now-iconic origami crane, which has become a symbol of peace, healing, and hope.

Origami as a Cultural and Artistic Practice

By the Edo period (1603–1868), paper had become more affordable, allowing origami to move beyond the elite classes and into the hands of common people. Recreational folding became popular, often taught to children and passed down through generations as a form of storytelling and cultural continuity. The folds were simple and largely based on animals, flowers, and daily life.

During this time, origami was also influenced by religious and ceremonial practices, particularly Shintoism, where folded paper strips known as shide were used to mark sacred spaces.

Despite the growing interest, these early forms of origami lacked the formal system of standardized folds and diagrams that we associate with the art today. That development would come much later.

European Paper Folding Traditions

While Japan was cultivating origami, similar practices were developing independently in Europe. By the 12th century, the Moors introduced paper to the Iberian Peninsula, and folded paper art began to appear in Spain and other parts of Europe. One prominent example is papiroflexia or pajarita, a traditional Spanish form of paper folding that includes the famous folded bird called La Pajarita.

In Germany, Friedrich Fröbel, the founder of the kindergarten system in the 19th century, recognized paper folding as an educational tool. His introduction of folded models as part of early childhood education laid the foundation for the use of origami in teaching geometry, creativity, and manual dexterity.

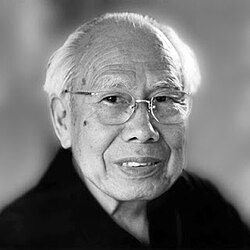

The Modernization of Origami: Akira Yoshizawa and the 20th Century

The individual most credited with transforming origami into a modern art form is Akira Yoshizawa (1911–2005), a Japanese artist whose influence is still felt today. Yoshizawa was largely self-taught and developed over 50,000 models during his lifetime. His work was not just artistic but deeply technical—he invented the technique of wet folding, which allows the paper to be dampened slightly to hold curved and sculptural shapes.

Yoshizawa also introduced a notation system, now known as the Yoshizawa-Randlett system, which uses arrows and symbols to describe folds. This system, refined by Samuel Randlett and Robert Harbin, became the international standard and enabled the sharing of complex models across languages and cultures.

Through exhibitions and international collaborations, Yoshizawa helped popularize origami around the world, elevating it from a folk craft to a serious art form.

The Global Spread and Scientific Intersection

By the mid-20th century, origami had attracted interest from not only artists but also scientists, mathematicians, and engineers. Mathematicians like Robert Lang and Erik Demaine have used origami principles to explore geometry, algorithms, and structural engineering.

Lang, a physicist and origami master, has applied folding principles to everything from space telescope lenses to biomedical devices. His computer programs can calculate crease patterns for folding virtually any shape from a single sheet of paper.

Similarly, NASA has incorporated origami into its designs for solar panels and spacecraft components, maximizing size efficiency for launch and deployment. The intersection of origami and technology has given rise to computational origami, a field at the cutting edge of design and materials science.

Cultural and Social Impact

Origami has also played significant roles in social and emotional healing. After World War II, the origami crane became a symbol of peace, largely due to the story of Sadako Sasaki, a young girl who developed leukemia from radiation exposure after the Hiroshima bombing. Inspired by the Japanese legend that folding 1,000 cranes grants a wish, Sadako’s story became a worldwide call for nuclear disarmament and peace. Today, the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima receives thousands of paper cranes each year.

In classrooms, origami is used to develop spatial skills, patience, and focus. In therapy settings, it’s used to aid mental health and rehabilitation. As a cross-cultural symbol, origami embodies mindfulness, transformation, and unity.

Conclusion: From Ancient Ritual to Contemporary Innovation

The history of origami is a testament to human creativity and adaptability. What began as ritualistic folding in religious ceremonies has evolved into a multifaceted discipline that spans art, science, and education. Its simplicity—a single sheet of paper, folded without cuts—belies the complexity and depth of its impact across cultures and centuries.

Origami continues to grow and inspire, from the hands of children making paper boats to scientists designing foldable satellites. Its journey reflects not only the evolution of an art form but the story of global connection through the universal language of folded paper.

References (for further reading):

- “Origami Design Secrets” by Robert J. Lang

- “Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes” by Eleanor Coerr

- The Origami Resource Center: https://origami-resource-center.com

- The British Origami Society: https://www.britishorigami.org.uk

- Smithsonian Institution Archives: Materials on Akira Yoshizawa