Stanley Kubrick was an acclaimed American filmmaker, frequently hailed as the greatest American director of his era, who virtually reinvented each genre he worked in, from horror to science fiction, and even redefined psychological drama. His career was characterized by a preoccupation with moral and social issues, coupled with an unsurpassed technical artistry.

Early Career and Formative Experiences

Born in the Bronx, New York, on July 26, 1928, Kubrick’s passion for visual storytelling began early. At 13, his father, a physician and amateur photographer, gave him a Graflex camera, leading young Stanley to become a photographer for his high school newspaper. At 17, he secured a job at Look magazine, an experience he found invaluable for learning about photography and gaining insights into how the world worked and people behaved. This period honed his ability to direct star personalities during photo shoots, preparing him for working with actors later in his film career.

Kubrick transitioned from still photography to filmmaking, initially funding his projects himself. He spent $3,900 to make his first documentary short, “Day of the Fight” (1950), about boxer Walter Cartier, and sold it for $4,000 to RKO Pathé News, proving himself as a profitable filmmaker at age 20. He followed this with “Flying Padre” (1951), about a New Mexico priest who flies to his parishioners, on which he broke even. His third and final documentary short, “The Seafarers” (1953), commissioned by the Seafarers International Union, allowed him to gain valuable experience working in color, despite having little editorial control.

He then borrowed $10,000 from his father and uncle to make his first independent feature film, “Fear and Desire” (1953). Kubrick made the film almost single-handedly, serving as cameraman, sound man, and editor, in addition to directing. Despite later considering it “inept and pretentious,” the film provided him with invaluable experience. Its distributor, Joseph Burstyn, lauded Kubrick as “a genius” and the film as “an American art picture without any artiness”. For his second feature, “Killer’s Kiss” (1955), a film noir, Kubrick again handled most production chores himself and shot on location in New York’s shabbier sections for visual realism.

Kubrick’s collaboration with producer James B. Harris began with “The Killing” (1956), a racetrack heist thriller adapted from Lionel White’s novel Clean Break. Kubrick, along with novelist Jim Thompson, was credited with “additional dialogue”. The film’s non-linear narrative, using fragmented flashbacks, was initially criticized but Kubrick insisted on retaining it, believing it elevated the film beyond a mere crime picture. Time magazine compared Kubrick to the young Orson Welles for his imaginative dialogue and camera work.

Artistic Breakthroughs and Thematic Preoccupations

Kubrick’s career truly took flight with “Paths of Glory” (1957), an uncompromising anti-war film adapted from Humphrey Cobb’s 1935 novel. The film, co-written with Calder Willingham and Jim Thompson, devastatingly critiques military hierarchies and class systems during World War I. Its narrative is divided into three parts: the lead-up to a suicidal attack, the disastrous attack itself, and the subsequent court-martial and execution of three soldiers chosen almost at random for “dereliction of duty”. Despite the French government banning the film for 20 years due to its depiction of the French army, “Paths of Glory” is widely considered one of the best films about World War I.

Kirk Douglas, who starred in Paths of Glory, brought Kubrick onto his next project, “Spartacus” (1960), after director Anthony Mann quit. This epic account of a Roman gladiator leading a slave revolt cemented Kubrick’s desire for absolute creative control. His inability to exert full control over the studio’s final cut led him to move permanently to England, directing from there for the rest of his career, at an “ocean and a continent’s distance from Hollywood”.

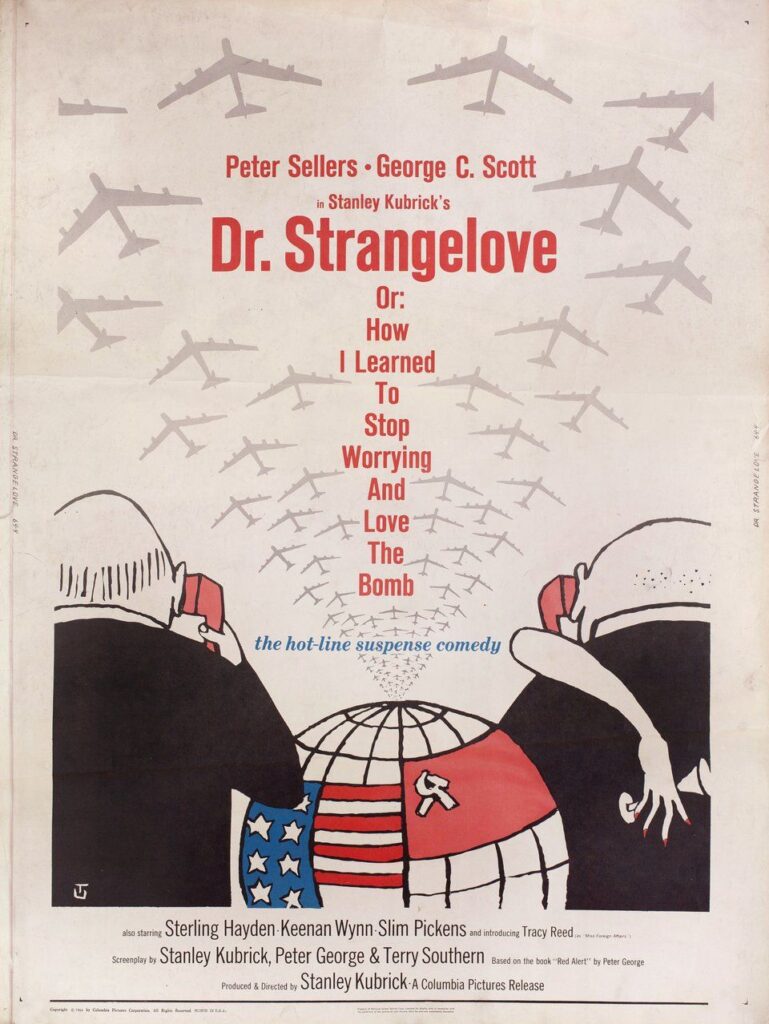

Kubrick’s next film, “Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” (1964), marked a significant shift in tone and genre. Co-written with Terry Southern and Peter George, it transformed George’s serious novel Red Alert into a “nightmare comedy” about accidental nuclear war. Peter Sellers, playing multiple roles, delivered brilliant improvised comedic performances, making him the perfect ally for Kubrick, who believed comedy allowed him to deal with otherwise unbearable issues.

Four years later, Kubrick released “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), a groundbreaking science fiction epic developed with author Arthur C. Clarke from his short story “The Sentinel”. The film explores themes of intelligent life beyond Earth, human evolution, and artificial intelligence, using evocative visuals rather than a deliberate narrative. Kubrick famously removed all explanatory narration, aiming to communicate more to the “subconscious and to the feelings than to the intellect”. Initially receiving mixed reviews, 2001 gained a large, appreciative audience and is now recognized as a technical masterpiece.

Later Works and Enduring Legacy

Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” (1971), adapted from Anthony Burgess’s novella, provoked immense controversy due to its unsparing depiction of violence. The film explores themes of free will versus state-imposed psychological conditioning, with Kubrick asserting that “to restrain a man is not to redeem him. Redemption…must come from within”. The film’s withdrawal from distribution in Great Britain in 1974 was due to death threats against Kubrick and his family, a fact later substantiated by his adopted daughter Katharina Kubrick and longtime assistant Anthony Frewin.

“Barry Lyndon” (1975), an adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s picaresque novel, showcased Kubrick’s meticulous attention to historical detail and stunning cinematography by John Alcott, who sought to simulate natural light of the 18th century. Although initially receiving a lukewarm reception, its reputation has steadily improved over the years.

“The Shining” (1980), based on Stephen King’s novel, delved into psychological horror, focusing on a writer’s descent into madness while isolated in a snowbound hotel. Despite its popular success, King himself expressed reservations about Kubrick’s adaptation, feeling it abandoned the empathetic relationship between characters found in his novel.

Kubrick returned to anti-war themes with “Full Metal Jacket” (1987), co-written with Michael Herr and Gustav Hasford, from Hasford’s novel The Short-Timers. The film examines the dehumanizing process of boot camp and the duality of man, epitomized by Private Joker’s “Born to Kill” helmet and peace button.

His final film, “Eyes Wide Shut” (1999), based on Arthur Schnitzler’s novella Traumnovelle, was a psychological drama dealing with sexual obsession and jealousy. Kubrick meticulously oversaw every aspect of production, often operating the camera himself and rewriting the script during filming. The film was delivered to Warner Bros. just four days before his death in March 1999.

Despite media portrayal as a “recluse,” those who knew Kubrick, such as his assistant Anthony Frewin and his family, stated he was far from a hermit. He preferred to work from his country home near London, but was very communicative with his collaborators. His insistence on multiple takes (“Forty-Take Kubrick”) stemmed from his perfectionism, aiming to ensure that every shade of meaning intended by the scriptwriter came across.

Kubrick’s influence on cinema is undeniable. He received numerous accolades throughout his career, including the Luchino Visconti Award in 1988 and the Life Achievement Award from the Directors Guild of America in 1997. He believed a compelling storyline was key to a successful film, and that a filmmaker’s goal was “to make the ordinary extraordinary”. His canon of pictures testifies to his valuing artistic freedom and his dedication to creating films that stimulated audiences to think about serious human problems. His legacy is encapsulated by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ description of his career as “unique achievements of his entire career and his lifetime contribution to the art of the film”.