There is an old saying that you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover. Yet history shows we do exactly that—sometimes to the point of banning a book not for its words, but for the artwork on its jacket. The art of the banned book cover is a curious, often absurd reflection of cultural anxieties: the way a painted shoulder, a too-bold font, or a suggestive sketch can trigger moral outrage as easily as any scandalous sentence buried inside.

When the Picture Speaks Louder than the Text

In the 20th century, publishers quickly discovered that a book cover could be more dangerous than the narrative itself. While prose might skirt censors, the artwork on the wrapper often screamed too loudly.

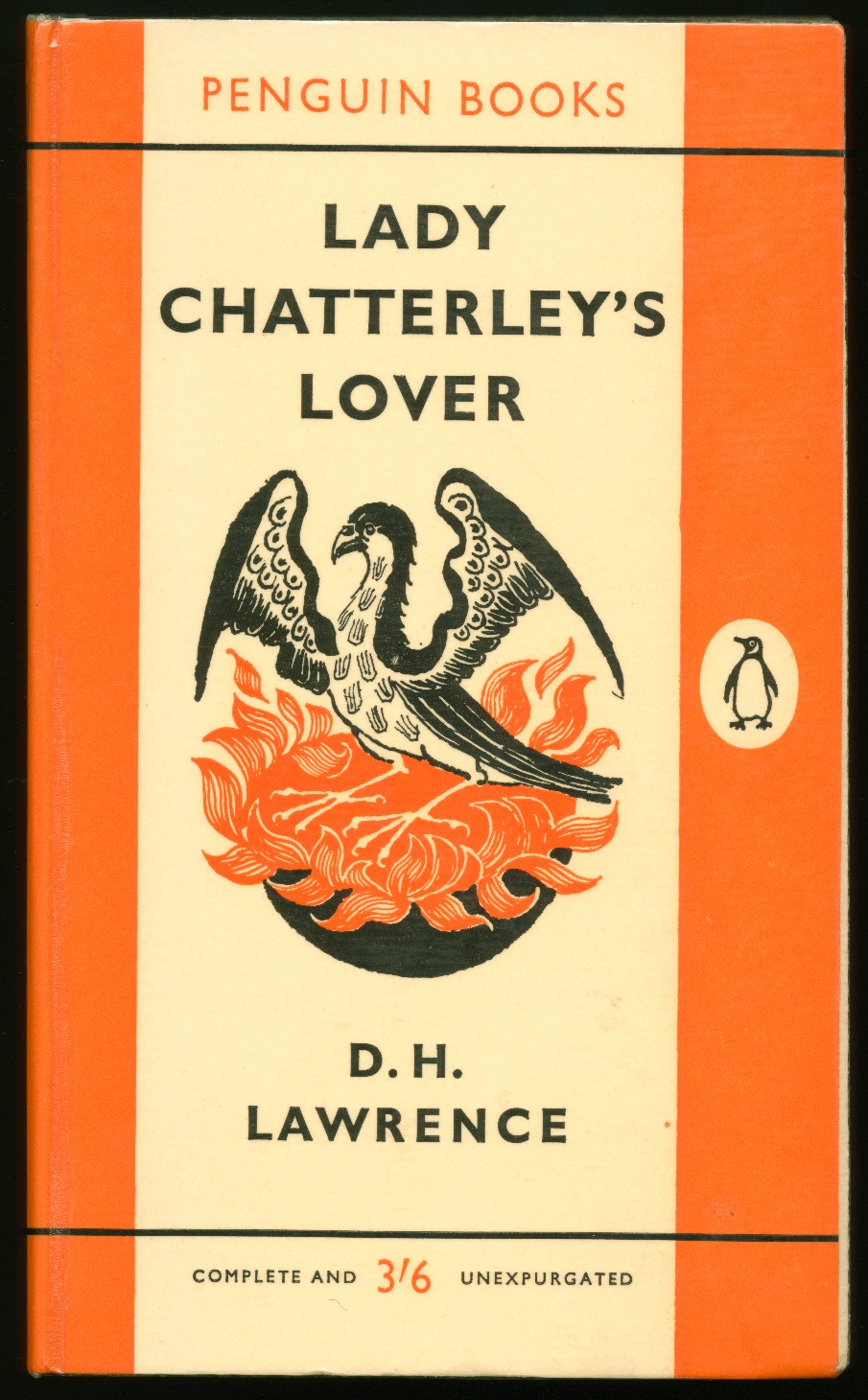

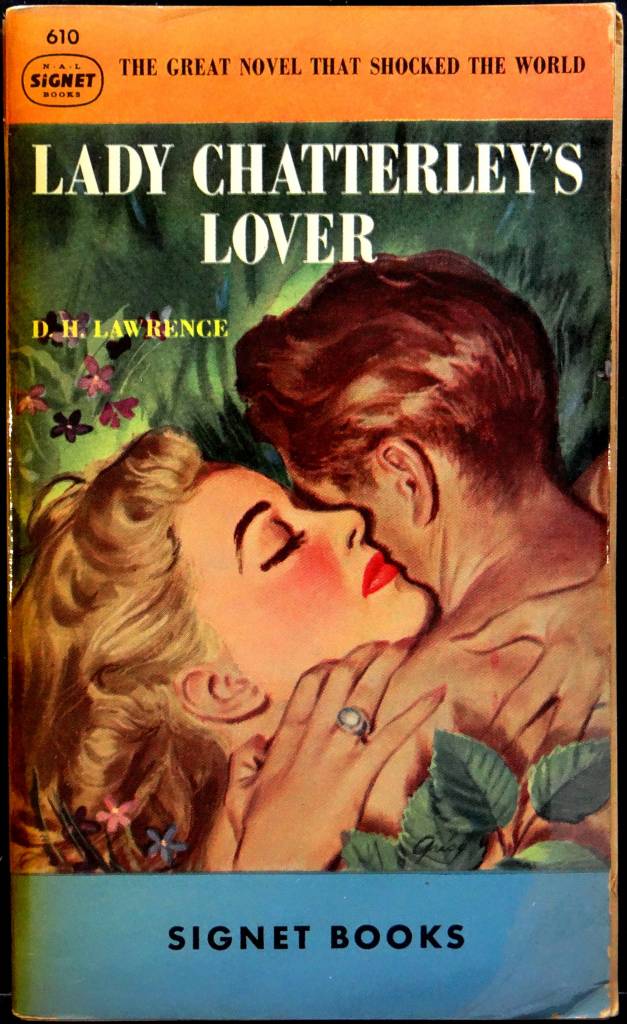

Take Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928). Before its landmark obscenity trial in 1960, editions were smuggled in with discreet jackets. Yet when publishers dared to adorn it with images of nude figures in pastoral embrace, booksellers faced seizures and fines. A single cover was seen as more scandalous than Lawrence’s actual descriptions of intimacy.

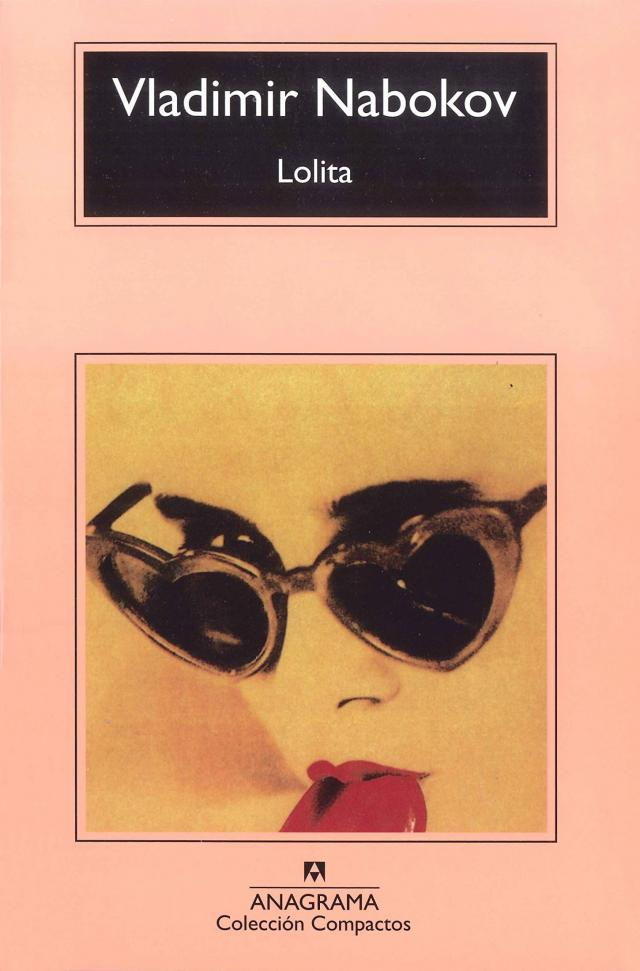

Or Lolita (1955). Nabokov famously detested the lurid illustrations publishers proposed, fearing they would cheapen his novel into pulp. In France, one early edition featured a cartoonish, barely pubescent girl—so provocative that Nabokov called it “abominable.” The now-iconic cover—heart-shaped sunglasses—arrived only in 1966, transforming into cultural shorthand for dangerous desire.

Pulp, Panic, and the Marketing of Sin

The paperback revolution of the 1940s and ’50s was a carnival of censorship battles. Covers had to sell books from crowded racks, and artists leaned hard into provocation.

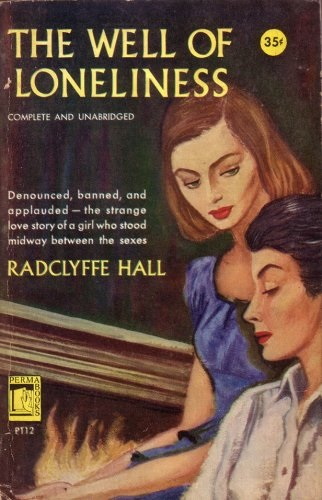

- The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1928) was banned in Britain for its lesbian themes. But when it re-emerged in paperback decades later, publishers leaned into controversy, using shadowy silhouettes of two women in close embrace. These covers were quietly pulled in conservative towns.

- Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith (1944), a novel about interracial love, provoked furious backlash in the American South. While the text was already taboo, the cover art—featuring entwined Black and white bodies—was enough to get the book banned in Boston.

- Mid-century pulp novels like Women’s Barracks (1950) flaunted covers of women in lingerie, designed to titillate male buyers while slyly signaling queer themes. Some editions were seized at the border as “obscene,” yet these covers are now prized artifacts of hidden LGBTQ history.

Even science fiction wasn’t safe. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 has been published with covers showing burning books and, in one infamous edition, a nude woman rising from the flames. Schools banned it not for the text’s anti-censorship message but for the imagery.

What a Banned Cover Really Reveals

If the text of a novel can be read as a record of its time, the banned cover is its cultural echo. The pearl-clutching over a risqué sketch in 1955 reveals the era’s fragile moral codes; the outrage at psychedelic, drug-influenced designs of the 1960s points to fears of rebellion and youth culture.

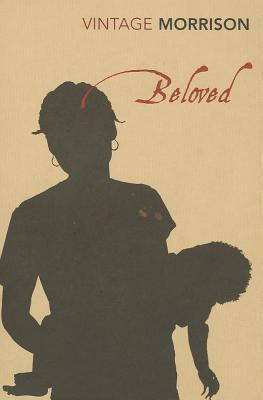

Sometimes, the controversy wasn’t about sex at all. When Toni Morrison’s Beloved was released in the late 1980s, some bookstores refused to display editions featuring the haunting image of a Black mother holding her child, claiming the cover was “too disturbing.” Visibility itself—whether of race, gender, or desire—was treated as dangerous.

From Outrage to Iconography

Ironically, many of these once-banned covers now hang in galleries or sell for thousands at auction. The pulp cheesecake paintings of Robert Maguire or James Avati—once denounced as smut—are celebrated as mid-century Americana. Nabokov’s despised Lolita sunglasses cover has been endlessly reinterpreted in fashion shoots and film posters. What was scandal yesterday is nostalgia today.

Judging by the Wrapper

Ultimately, the history of banned book covers is a reminder of the power of the image. Words may take a few pages to unsettle, but a picture provokes instantly. That’s why a cover is not merely marketing but cultural performance—an aesthetic statement about what the book is, and what it dares to suggest.

To judge a novel by its controversial wrapper is to participate in this history of moral panic and shifting values. What once scandalized now seems silly, even charming. But that cycle of outrage tells us something important: art, even when reduced to a few square inches on a paperback, has always had the ability to disturb, provoke, and expose the fault lines of society.

In the end, perhaps the most radical covers are not the ones that shock, but the ones that reveal just how easily we are shocked.

Let’s tour the exhibit page-by-page:

Exhibit: Controversial Covers That Captured Cultural Outrage

1. Lolita (1955) — Heart-Shaped Sunglasses

This iconic cover—featuring nothing but red heart-shaped sunglasses—has become shorthand for the novel’s provocative themes, without a single depiction of its controversial subject. Nabokov himself disapproved of earlier lurid illustrations, concerned they reduced his literary work to mere sensationalism. Wikipedia

Its simplicity and enduring visual power show how a well-designed symbol can outlive its scandal and enter cultural legend.

2. Lady Chatterley’s Lover (Penguin editions)

These editions, especially those around 1960, were marked by subtle yet suggestive artistry—romantic but transgressive for their time. Early U.K. versions led to prosecutions and public uproars, reminding collectors of how far cultural sensibilities have shifted. Max RambodWikipedia

3. Lady Chatterley’s Lover (Reissue paperback)

Bold, expressive, and unmistakably sensual—this cover reflects the paperback revolution’s drive to capture reader attention in crowded racks. Though modest by today’s standards, such imagery once stoked fears over moral decay.

4. Another Lady Chatterley’s Lover variant

Further variations in cover styles—from suggestive flourishes to romantic tableaux—demonstrate the evolving balance between marketability and censorship. Each version embodies a moment in the tug-of-war between cultural conservatism and artistic representation.

Contextual Highlights & Historical Depth

Women’s Barracks (1950)

Cover Art & Controversy: Designed by Baryè Phillips, this cover depicted women in various states of undress, clearly signaling the lesbian subtext. It became a defining image of pulp erotica and was banned in Canada. Its popularity even prompted the formation of the U.S. House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials. Wikipedia

Strange Fruit (1944) by Lillian Smith

Content & Censorship: Featuring an interracial romance, the novel was banned in Boston and Detroit for “lewdness,” despite the lack of explicit sexual scenes. The U.S. Postal Service even stopped mailing it until Eleanor Roosevelt intervened with President Roosevelt. Wikipedia+1DBpedia Association

The Well of Loneliness (1928)

Visual Silence & Legal Clash: Though less focused on cover imagery, this lesbian-themed novel ignited a major obscenity trial in the U.K. because its mere existence—and any visible hints toward its subject matter—were enough to challenge societal norms. Esteemed figures like Virginia Woolf testified in its defense. Wikipedia

Why These Covers Still Matter

| Element | Why It’s Significant |

|---|---|

| Instant Emotional Punch | A provocative image can stir public emotion more readily than pages of text. |

| Cultural Mirror | Controversy around covers reflects societal fears—sexuality, race, desire—in a distilled form. |

| Marketing Power | Scandal sells. What’s banned often becomes more coveted. |

| Time’s Judgment | Cover art once deemed obscene may later be seen as kitschy or historically rich. |

| Symbolic Evolution | Some designs (like the Lolita sunglasses) transcend scandal to become cultural icons. |

In curating this visual essay, the covers become artifacts of shifting morality, marketing ingenuity, and cultural tension. Through them, one can trace how art, commerce, and censorship collided—and how images, perhaps even more than text, revealed society’s deepest anxieties.

Mini-gallery • Books · Art · Culture

A deliberately plain, typographic wrapper—issued amid fears of censorship—proved that restraint can be just as incendiary as lurid illustration. Later sensational covers (and the 1962 film poster’s heart-shaped sunglasses) only amplified the myth.

A landmark of lesbian pulp. The suggestive tableau helped the book sell—and helped attract bans (including in Canada) and official scrutiny in the U.S., where it fueled hearings on “current pornographic materials.”

An understated jacket for a novel that triggered an obscenity trial in Britain. Proof that sometimes the controversy isn’t on the cover at all—the title alone became a cultural lightning rod.

A blunt promise on the wrapper—“unexpurgated”—helped set the stage for the 1960 UK obscenity trial that Penguin famously won. The cover is advertising and provocation in the same breath.

Why these covers?

They chart a zig-zag course through the last century’s moral panics: from pulp’s “marketing of sin” to typographic minimalism that still managed to scandalize. Some were banned outright, some quietly redesigned, and some—ironically— became design icons after their trials were over.

Gallery usage & credits

Images are embedded via Wikimedia Commons’ Special:FilePath (which serves the actual image file). Click any credit link to view the file page with licensing and provenance.