Considered an anti-comedy, and Krzysztof Kieslowski’s most straightforward and mainstream film, Three Colours: White, which deals with equality, is the second in the Three Colours trilogy.

Largely considered to be a black comedy, composed of darkly humourous moments, Three Colours: White is the second film in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s “Three Colours Trilogy” (the other two being Blue and Red), which deals with the idea of equality (the other two films deal with liberty and fraternity).

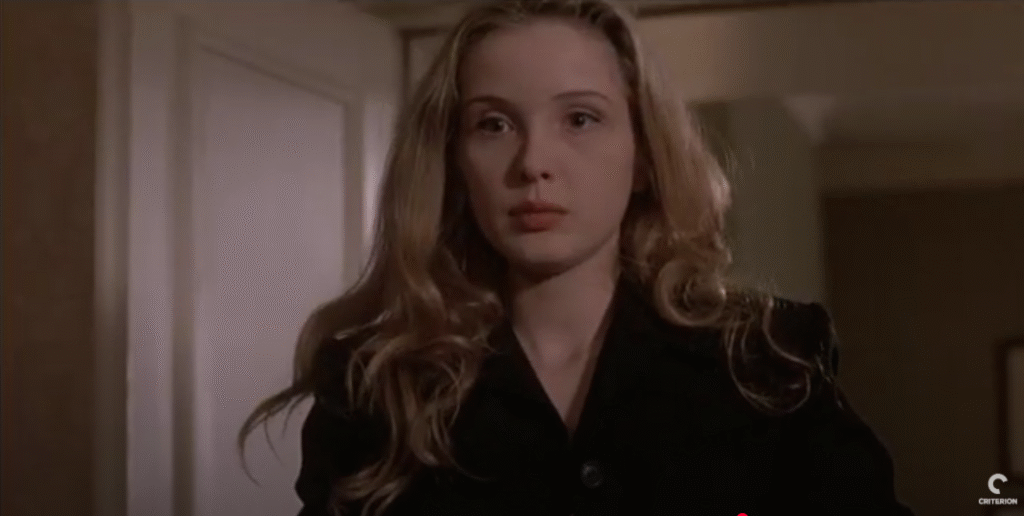

The films tells the ironic story of Karol Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski), an impotent Polish man, who, after his French wife, Dominique (Julie Delpy), divorces him, hatches an elaborate plot to regain equality in their relationship, the scheme verging on revenge and thereby ensuring a tragic blend of love and separation.

The story begins with a courtroom trial (the same one which Julie accidentally walks into, before being kicked out, in Blue). The Polish immigrant, Karol has trouble understanding French, but with the help of a translator is made to understand that his French wife does not love him anymore, and seeks divorce on the grounds that the marriage was never consummated- he is impotent. The divorce is granted, he loses his means of support (a beauty salon they jointly owned), his legal residency in France and the rest of his cash in a series of mishaps, and is soon on the streets with nothing but a 2 Franc coin.

He starts playing Polish folk songs on a comb in the Metro, for spare change, where he catches the attention of Mikolaj, a Polish bridge player who has an excellent memory. Mikolaj offers to take him back to Poland in a suitcase, and leave behind the alienation and isolation of France (Kieslowski’s true feelings of his adopted country, perhaps?).

Once the plane lands in Warsaw, Mikolaj learns that the luggage has gone missing. The suitcase is stolen by some baggage thieves, who try to rob Karol once they find him inside the suitcase. But he has nothing worth stealing, so they leave him in a garbage dump.

Anthony Leong observes:

Karol wakes up and sees the white snowswept garbage dump and cries out “home at last!”.

Karol stays at his brother’s house and works there for a while, before he gets inspired to regain his equality with Dominique: regain prestige and wealth and exact revenge on his ex-wife. Taking advantage of the new free market economy of post-communist Poland, Karol amasses a fortune with the help of the Polish Mafia and Mikolaj. He then fakes his own death, bequeathing his wealth to Dominique who comes to Poland for the funeral. But later that night, Karol appears in Dominique’s room, shocking her. They finally make love, consummating the marriage. In the morning, Karol is gone and Dominique is arrested for Karol’s ‘murder’.

The ending is simple. Karol goes to the prison where Dominique uses sign language to tell him that she still loves him, and, if she manages to get out of prison, is willing to marry him again. The final image of the film shows Karol staring at Dominique through the window of her prison cell, and crying.

The ending/ climax of the film was shot after the rest of the film, as Kieslowski wanted to soften Dominique’s image, and make her seem less of a monster. But the true ending of White is actually found at the end of Red, where it appears as though Karol and Dominique have indeed remarried.

Relatively simpler than Blue or Red in narrative, White oscillates often between comedy and tragedy. It does not contain the intricate metaphors like the other two films of the trilogy, but as Doug Cummings remarks:

…the cool machinations of its protagonist (as well as its storytelling) often seem manipulative and superficial, but Kieslowski’s pessimistic wit shines throughout.

However, because of its straightforward narrative style, it is widely considered as the most ‘mainstream’ of all of Kieslowski’s films.

There are essentially two things that came through in the film.

The first thing is a subtle take on the newly established free market system in Poland, following the fall of Communism.

One observes the remark in the film:

These days, you can buy anything!

It is true that it is only the free market that helps Karol amass his fortune. However, Karol himself remains disdainful of the system throughout.

Second is the simplistic manner in which Karol’s quest for equality is depicted. The 2 Franc coin becomes a symbol of that quest. While he is about to toss the coin into a river, it is at that moment that he comes up with the idea to regain equality in his relationship, and stops himself from tossing the coin away. Throughout the film he does not let the coin go. It is only after he inspects the body that will be buried in place of his (he is faking his own death), that he lets the coin go. The scene for me signifies that equality, that he seeks, has already been achieved. He has gained parity with Dominique, maybe not in terms of love, but at the moment, certainly in terms of spitefulness.

Karol realizes this at the end of the film, that even though he has avenged his ex-wife, he still loves her. As such the victory is nothing short of Pyrrhic.

Parity regained, but Paradise lost!