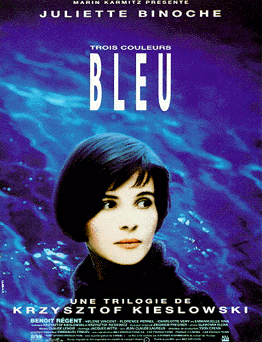

Three Colours: Blue is the first of last and finest of Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski’s works, the Three Colours trilogy. A masterpiece, representative of ‘film as literature’, this film is a true exploration of not just contemporary French society, or even its protagonist’s struggle to attain emotional freedom, but also of the audience’s understanding of ‘liberty’, love and human emotion.

The last set of work of the Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski was the trilogy Three Colours or Trois Couleurs, based loosely on his adaptation of the French Revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity to modern day Europe (the contemporary French society in particular). The trilogy takes its name from the colours of the French flag and its themes from the ideals represented by those colours: blue (liberty), white (equality), and red (fraternity).

Krzysztof Kieslowski’s “Three Colours Trilogy” was made back-to-back in 1993, following the success of his “Double Life of Veronique”. Three Colours: Blue, themed on liberty, is the first film in the trilogy. According to Kieślowski, however, the subject of the film is emotional liberty, rather than its social or political meaning.

Blue is set in modern-day Paris. Julie ( played by Juliet Binoche), at the start of the film (or one could say, at the start of the Trilogy) survives an automobile accident in which her husband, a famous composer, and their daughter are killed. The rest of the film depicts her desire, efforts, and the subsequent inability, to free herself of all emotional attachments, and alienate herself from the world around her. Initially, after her recovery in the hospital, she tries to kill herself by swallowing pain-killers, but does not succeed. She, in an effort to deride herself of all memories of the past, then packs up her family home, sells the furniture and moves to a small apartment in Paris, without telling anyone, or keeping any clothing or objects from her old life, except for a chandelier of blue beads that presumably belonged to her daughter.

She also destroys her late husband’s last composition, a piece for the festival of European Unity. Thereafter, she befriends Lucille, a prostitute/stripper that lives downstairs from her; falls in love with Olivier, her late husband’s aide; and helps Sandrine, the mistress of her late husband who is carrying his child.

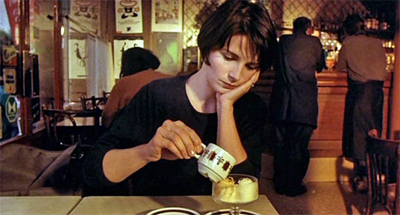

As foreshadowed by the title of the film itself, the predominant colour throughout the film is Blue. Whether it is the symbolism of her past life, through the chandelier of blue beads, or the colour of her late husband’s notes, blue is a constant noose choking Julie. Liberty that she so desperately is struggling to achieve, emotional bondage that she is so eager to escape, memories that she is running from, keep haunting her life in shades of blue. The struggle of colours is best symbolized in the scene where Julie, sitting inside a cafe, hears music similar to ones composed by her husband, and turns to find a beggar playing against a blue bespattered wall: almost as if celebrating the picture’s inherent ‘two-dimensionality’.

Anthony Leong writes:

It is a slow-moving film, in the typical French atmospheric style- a textured piece of cinema. It is an excellent example of what is described in “Film Art” by Bordwell and Thompson:

“every component functions as part of the overall pattern that is perceived… subject matter and abstract ideas all enter in to the total system of the artwork.”

Given its name, “Blue”, you cannot help but look for that colour in the film’s carefully-sculpted scenes. Of course, the trick that Kieslowski has pulled on you is that he is forcing you to PAY ATTENTION to what is happening on the screen. And because your awareness has been heightened by this trick, you begin to notice the clever tapestry of form and function of this film.

And the struggle does not end just there. Not just in colours, but the struggle between memories of the past, and the emotional freedom Julie desires, is also symbolized in sound: the present has sparse dialogues and little background music, while the memories quiver with the tunes of her husband’s compositions.

The concept of liberty itself is questioned: assuming Julie gets the ‘liberty’ she so desires, would it necessarily lead to happiness? Does she desire the liberty that now Julie’s mother, suffering from Alzheimer, has? The fact that the mother cannot recognize her own daughter acts as a metaphor of the lack of meaning in relationships if there is no acknowledgment of shared history.

There are many shots from a first-person perspective; extremely tight close-ups of mundane events include the viewer into Julie’s private world. For example, the shot of a sugar cube absorbing coffee.

And even this private world has shades of blue. The swimming pool which Julie frequents is an excellent metaphor for her introspection. She is always alone in the pool, bathed in a blue light, except for the scene where she speaks with Lucille. At one point, she immerses herself completely and stays underwater for as long as possible. But soon, she is compelled to come up for air: a sort of summary of the development of her character as the film unfolds.

Annette Insdorff writes in Double Lives, Second Chances: The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieslowski:

…the placid blue surface initially suggests escape, but it is precisely in the water that [Julie] twice gasps and stops, suddenly overcome by fragments of the unfinished concerto. With the accompanying blackouts, the pool symbolises the incomplete mourning as the space where Julie opts for physical exertion rather than emotional confrontation…

There is also intricate and subtle injection of intertextuality woven into the films of this trilogy, in order to establish some kind of narrative linkage between them. Julie walks into a courtroom looking for Sandrine, her late husband’s mistress. The viewer is briefly given a glimpse of a divorce trial, before an Officer shows Julie out. And this divorce trial becomes the opening scene of the second film Trois Couleurs: Blanc (Three Colours: White), where Dominique (Julie Delpy) is seen sitting with her lawyer, and Karol’s (Zbigniew Zamachowski) voice is heard arguing with the judge about ‘equality’. The deliberate intertextuality between the films, starting with this odd scene, becomes apparent in “White”, where Julie walks in on the trial in the background.

Doug Cummings writes:

The subject of Blue this film is every bit as metaphysical as The Double Life of Véronique, but it is rooted in a more accessible narrative concerning Julie…Through Kieslowski’s subtle plotting, however, like tentative roots from a sapling, Julie slowly reconnects to life through a developing compassion for others and her growing artistic compulsions. It’s a graceful evocation of the inescapable force of love and art upon the soul and the paradoxical joys to be found in sacrifice, boundaries, and emotional commitment…

A masterpiece, representative of ‘film as literature’, this film is a true exploration of not just contemporary French society, or even Julie’s struggle, but also of the audience’s understanding of ‘liberty’, love and human emotion. The film can be read at many levels, interpreted in many ways, but in the end, one thing is certain: it is one of the greatest European films ever made. And yet it is very easy to underrate Blue simply because of the fact that it gets eclipsed by the class of the other two films that follow in the trilogy.

I remember the film as bleak and cold in style…yet warmly optimistic in its outlook. It can only be symbolic then, that the film ends with a concerto with the following words accompanying the closing images (reminiscent of Hegel’s ‘existence depends on acknowledgment‘ philosophy ):

Though I have the gift of prophecy and understand all mysteries,

If I have not love, I am nothing.