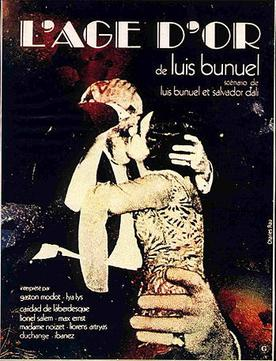

This surrealist film, directed by Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali, made in 1930, continues to shock, repel, scandalize cinema goers for over seventy-five years now. When L’Age d’Or had its first public showing in 1930—and its only public screening until 1979—it caused a riot. The film premiered at Studio 28 in Paris on November 29, 1930, after receiving its permit from the Board of Censors. In order to get the permit, Buñuel had to present the film to the Board as the dream of a madman. On 3 December 1930, a group of fascist League of Patriots threw purple ink at the screen, assaulted members of the audience, and later went to to destroy art works by Dali, Joan Miro, Man Ray, among other that were on display in the lobby. On 10 December, the Prefect of Police of Paris, Jean Chiappe, arranged to have the film banned. The producer of the film was threatened with excommunication. It also effectively killed Buñuel’s filmmaking career for nearly 20 years, until he was able to make Los Olvidados (1950) in Mexico. The film only premiered again in November, 1979.

And it is not hard to figure out why.

L’Âge d’or is a destructive and anarchic response to the strategies of containment and repression of what the surrealist movement of the late 1920s considered the corrupt technological age. A scabrous essay of Eros and Civilization before Freud’s psychological writing became popular, the film is at once a surrealist masterpiece celebrating Freud, anarchy, and is also a commentary on the nature of sexual oppression in a bourgeois society and the subsequent inevitability of violence as a sieve. There’s little discernible plot, and the film shifts gears constantly, mutating freely from one genre to the next seeking to outrage the viewer. Constructed in the form of loosely connected vignettes, the film (not having any plot whatsoever) tells the tale (tentatively) of a couple, who are always thwarted in their efforts to make love: the lovers are introduced into the narrative while rolling in the mud. As far as their part in the film is concerned, they start out making love in a manner that disrupts a nationalist religious ceremony, are pulled apart, and spend the bulk of the film trying to get back together.

Luis Bunuel himself reveals in his autobiography, My Last Breath: “Our sexual desire has to be seen as the product of centuries of repressive and emasculating Catholicism. It is always colored by the sweet secret sense of sin….”

Throughout the film, the pair are forced to defer the consummation of their passion, which leads to certain erotic displacements, and subsequent instances of fetishism, the most prominent example of which takes place in the scene where the woman performs fellatio on the toes of a statue of Venus. Another instance is the sequence where Modot, the male lover, becomes transfixed by various advertising images in the street. In a Barthesian comedy of errors, these signs of commercial mass-production transform into highly-charged masturbatory images in the mind’s eye of the anthropomorphous protagonist.

The tale unfolds as a surreal, dreamlike, deliberately pornographic and blasphemous work. The first sequence is shown in the form of “found footage” of a group of scorpions, with commentary added by Bunuel himself. The film then goes on to show four bishops decomposing on the rocks. Then the leader of a group of bandits cries “To arms!”. Yet instead of an invading army, a seemingly benign horde of Majorcan civilians in smart street clothes swarm over the rocks like ants. Humans are insects. As the band of delirious troops die one by one, the futility of their battle becomes apparent. There seems to be no need for fighting when the enemy is capable of devouring itself.

In a sudden moment of rage, the frustrated lover, stamps on a humble beetle. Later, this action finds a parallel in a passer-by who takes his rage out on a violin. In an orgasmic moment, the female lover exclaims “What joy to have murdered our children!” as an earlier scene where a Gamekeeper cuddles his son, then following the boys petulance, takes pot shots at him with a revolver, is brought to the mind.

The final sequence shows an orgy lasting 120 days, after which the survivors of the orgy emerge. From the door of a castle emerges the Duc de Blangis, who strongly resembles Christ. When a young girl runs out of the castle, the Duc comforts the girl, before taking her back into the castle. A scream is heard and the Duc emerges again, his beard mysteriously vanished. The film’s final image shows scalps of the women flapping in the wind on a crucifix, accompanied by jovial music. But there is some comfort in the fact that by the time L’Age d’Or gets to its incredibly blasphemous conclusion, it has attacked nearly every moral and religious taboo you can imagine.

Elisabeth Lyon writes: “Bunuel continually manipulates time, space and mise en scène to pervert the logic of narrative continuity. His structuring device is the faux raccord, mismatches that produce oneiric, transformed images of reality.”

Be it images of a toy giraffe flying out the window, to become a real one, or the images of the man striking his lover’s mother after she spills wine on his hands, there is a pervading sense of relentless assault on the repressive social strategies of the bourgeoisie, in a “purposefully blasphemous and corrosive work that attacks social institutions with such vigor and imagination that one cannot help but be entertained”.

The conclusion, simply put, a prominent film critic jocularly remarks: “Love it, hate it or be merely baffled by it, you’ll finally admit that there’s really nothing like it in the history of film.”