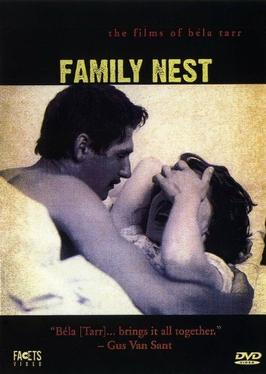

Family Nest is a Hungarian film, directed by Bela Tarr in 1979, which shows the domestic problems of Laci (László Horváth), a soldier who has just returned home, and his wife Irén (Laszlone Horvath), set among the backdrop of an increasingly lackadaisical bureaucratic system and troubles of getting a flat sanctioned from the government. He was only twenty-two years old when he made this landmark film.

The protagonist, Laci, is a victim, one of the thousands, of the aftershock of the Hungarian housing project. His wife has been living in her father-in-law’s pad for the entire time Laci was away. There is discord in the relationship between Iren and Laci’s father, who insists that she raise her daughter exactly the way he wants. He also dislikes the fact that she sometimes brings some of her coworkers home after work. Furthermore, later we see him poisoning Laci’s ears with claims that she has been cheating on him as she has been out, on a number of occasions, at night.

When Laci comes home, the couple start looking for a flat of their own. It is the perfect solution, if they do not want their relationship and their daughter to suffer. But it is a dream to get a flat, more than anything else. Tarr displays, with a finesse quite uncommon in filmmakers that young, the heartlessness of the government’s bureaucracy. His dissection of the scio-economic conditions of Hungary at the time, is indeed praiseworthy. Time and time again, Iren goes to the official begging him to do something, or else her family would tear apart. But the official, a low-ranked worker himself, cannot do much more than tell her his hands are tied. Outside, the camera would catch, quite innocently, other women telling their plights on the housing problem. For example, how one of the women was forced to squat in a vacant flat, to miserable results. Here Tarr seems to be working on two levels: the plight of the house-needy residents, and also the virtually useless office workers forced to hear out the complaints and the destroyed lives of those in the mercy of an impersonal society.

The use of camera is quite unique as well. The creation of a tense and claustrophobic diegetic space through very tight close-ups of faces and hands, and the loud commotion, during meals, subjects the viewer to almost the same conditions that the family itself is subject to. It transports the viewer into a world where he would generally not go, given the option. It is a society’s nightmare, which Tarr displays here. There is just too many people in too little a space, too much noise, and too much alcohol, and at the same time just not enough room or privacy for a family to live healthily.

There is an interesting scene in the movie, where Laci’s father glues together broken glass pieces of a picture of the Hungarian national flag. The nation building effort made by the working-class in represented here. And at the same time it is an interesting trivia to note that the glue that was used was called “Technocol”. It was the only glue that was available. It was the only glue that the government manufactured at the time. It was used for everything. It was a common man’s must-have. The symbolism in the scene then becomes apparent. Tarr sees it as truthfully as any filmmaker could and his camera shoots it with any cinematic falsity distilled from the scenario.

It is also a devastating portrayal of the sexism of the times. The male characters, especially Laci’s father, emerge as macho, sexists, hypocritical and at times violent characters, prone to drink and that toxic mixture of sentimentality, chauvinism and lust.

This directorial debut by Tarr immediately raised comparisons between others like John Cassavetes, an influence Tarr claims he was yet to discover. The kitchen-sink approach to realism may remind some of the work of the great Ken Loach (the use of non-professional actors for example) and there is certainly no denying that a powerful raw emotion is on display here. Later on Tarr would build a unique style of his own. He also would prove to be a source of inspiration for may great filmmakers like Gus Van Sant, Lav Diaz, and perhaps Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

What is even more interesting is the fact that entire film was shot on absolutely no budget, with non-professional actors, who only worked for “friendship’s sake” in the film, and not for any amount of money.

A truly wonderful first feature.