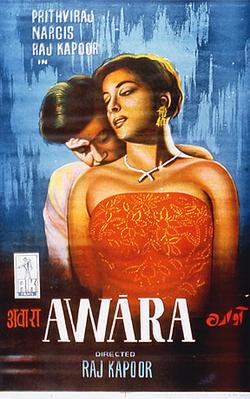

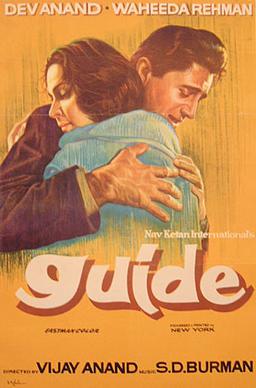

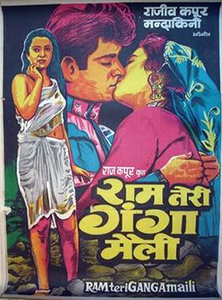

This essay explores and reflects on the change in the viewing and depiction of the ‘ideal’ woman in Hindi cinema from the demure in 1950’s to the brave and sexually liberated by the 1980’s as seen through the song and dance sequences of Hindi films, in particular,“Awara” (1951), “Guide” (1965), and “Ram Teri Ganga Maili” (1985).

Hindi cinema has borrowed substantially from the traditional theatric roots. As such, the image of the ‘ideal’ woman in Hindi cinema was constructed around the image of Sita and Radha from Indian epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata. However, in later years this image began to change.

In this essay, I state that the depiction of the ‘ideal’ woman in popular Hindi cinema changed from that of the demure, docile virgin to that of the sexually sovereign. I examine in the following essay, this phenomenon, looking closely at three particular song and dance sequences, one each from the films Awara (1951), Guide (1965), and Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985). The three songs I study closely are “Dam bhar jo udhar munh phere” form Awara, “Aaj phir jeene ki tamanna hai” from Guide, and “Tujhe bulayen ye meri bahein” from Ram Teri Ganga Maili.

I look at the scopophilic devices of sexuality and voyeurism, while examining the three songs, and how fetishism is used to manufacture cinephilia, and how fragmenting of the woman’s body leads to voyeuristic gazes.

My aim is to display the transition of the feminine ‘ideal’ in Hindi Cinema. And my conclusion sums up the study of these two devices, namely voyeurism and sexual fetishism, and how they shaped and affected this transition.

1. Introduction.

The early Indian Cinema, from the rise of the popularly called “Talkies revolution” in the 1930’s, traversing the 1950’s, called the “Golden Age of popular Hindi cinema” depicted women as essentially two archetypal characters. The first was that of the demure, ideal, obedient wife or lover of the hero, that was willing to die before giving up her ‘honour’, and the epitome of whatever value the Hindu patriarchal system held in high esteem. The second was the diametric opposite diegetic ‘western-influenced’ seductress, often of Anglo-Indian origin, “with names like ‘Rosie’ or ‘Mary’”, who was the narrative epitome of all that was considered to be morally unhealthy to the civil fibre. As such, the diegetic equilibrium was maintained through the concentration of the voyeuristic gaze on the vamp, through the song and dance sequences that took place often in a bar, or the villain’s hideout, or on a stage with leering on-screen crowd of men, while attempting to incite pathos, empathy, and feed the stereotypical image of the ideal woman, by depicting the heroine as virtuous, obedient, self-sacrificing. However, as the nation began to rise to a new awareness of itself, the image and portrayal of these women began to change. Even the heroines of the film became subject to the voyeuristic gaze of the spectator, whether diegetic or the actual one watching the film in a theatre. This transition started during the “Golden Age” itself with Awara, and gained prominence in Guide and reached its zenith in Ram Teri Ganga Maili. The song and dance sequences derived their inspiration directly from traditional sources, and became an essential part of the spectator’s experience in the cinema. In some films, their function was often to take the narratives forward, or to create a brief distraction from the tense narratives, or to convey a certain mood or mood transition. The most commonly used and experienced function, however, was to depict sexual interactions, without showing anything explicit. Thoraval writes:

− “For a spectator used to a linear narrative style, these intrusions can seem very abrupt and distracting because the dramatic action suddenly stops, the emotional flow is suddenly cut off at a certain point of action, and the song presents and develops and tries to communicate the rasa to the spectator.”

Rasa: Yves Thoraval explains rasa as “a fundamental notion of Indian aesthetics”, which describes “a kind of ‘subjective state’ of the audience/ listener/ or reader”. He points out various rasas: “the erotic, the pathetic, the heroic, serenity, repulsion, wonderment, etc.”

In this essay, I seek to examine this transition, looking in general at the state of the industry at the time, and in particular, at the the above mentioned films as case studies, with special attention given to the song and dance sequences of these films, in an attempt to demonstrate this shift in diegetic representation of the ‘ideal’ woman.

2. Sexuality.

Various film historians have traced the creation of the Indian female ideal to the mythological epitomes of virtue such as Sita, the wife of Lord Rama, and Radha, Lord Krishna’s lover. The myths of Ramayana and Mahabharata, two Indian epics, which are held very sacred and rooted deep in the Hindu society, have provided the society with its moral code, for centuries. Many theatre and musical art forms derive their inspiration from these epics, such as the Kathakali in Kerala, Lila in Orissa, Tamasha in Maharshtra and other regional theatre forms, known as ‘nataks’ or ‘nautankis’. Consequently, when cinema arrived in India, it remained rooted to the myths and the theatric traditions it borrowed so much from. These myths of Sita as the perfect wife, Radha as the perfect lover, virtuous and docile, faithful and obedient to their husbands, created the image of the perfect wife or lover as themselves. As such, explicit scenes of sex were banned as soon as film came to India, because of the fear of such ‘western influences’ destroying the moral code of the society.

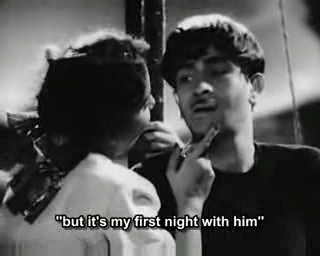

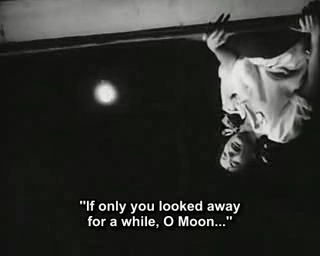

However, starting in the 1950’s, the song and dance sequences began to address sexuality in a very suggestive manner. In Awara, the couple, Raj, played by Raj Kapoor himself, and Rita, played by Nargis, are shown in the song “Dum bhar udhar jo munh phere” to be alone on a boat at night singing the song, and asking the moon to hide behind the clouds for a brief moment so that they can make love. What is most striking about the song is the fact that although there are a lot of sexual undercurrents recurrent throughout the song, visually there is not so much as a respectable kiss involved. However, the sexuality is brought about by suggestion. Rita declares to the audience, through the lyrics of the song, that it is her first night with Raj.

She has also mentioned to Raj that it is the eve of her twenty-first birthday. Gayatri Chatterjee points out that by the time the song occurs in the film, a substantial amount of transformation has taken place in the characters. Rita has ceased to be the strong and dignified lawyer, who did not wear any make-up at the beginning of the film, and now returns to the patriarchal interpretation of her image of femininity, while Raj becomes dignified after living the life of a tramp, in some sense.

− “But now in the song, Rita discards totally her lawyer self and wants to hide her act from the society, and enter into an illegitimate act.”

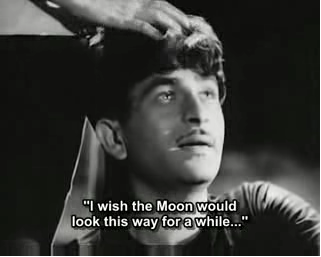

In discarding her dignified self, she puts on a very child-like attitude, carefree and innocent, at the same time remaining strong and mature enough to make her own decisions, with regards to the most taboo subject in the society, namely her, a woman’s, sexuality. Within the song, the prime example of suggestive sexuality takes place during the sequence, which starts with the close-up of Raj’s face, and Rita’s hand, from the top left corner of the frame, ruffling his hair. Raj then raises his right hand and pulls her by her wrists down closer to himself, the cut bringing them to a medium close-up at the cetre of the screen.

Sequence 1 from Awara (1951)

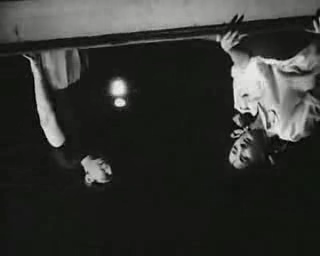

The lyrics accompanying this event is “Main tumse pyaar kar lunga”. At this point when, the two are framed in medium close-up, Rita’s face turned away from the camera, looking toward Raj, who keeps on coming closer and closer to her face. And just at the point where, a kiss would have occurred, Rita pulls away, and the next frame shows clouds covering the moon. This visual interruption of normal narrative ending in something expected does not, however, stop the spectator from imagining the following sequence of events. The moon becomes clouded after the couple imploring it to hide away for a brief period of time, just when they are about to kiss.

Sequence 2 from Awara (1951)

The suggestive nature of such a sequence creates a divide between the visual and the imagined, simultaneously disrupting the obvious flow of diegetic narrative and adding the imagined sequence to the storyline. Such a device increases spectators’ participation the flow of events. This particular cinematic device has been referred to as “coitus interruptus” by Gopalan, equating it with the contraceptive device, where the camera changes focus and “withdraws just before we see a sexually explicit scene”.

Similarly, the end of the song sequence shows long shot of the couple’s reflection in the water, with the moon between them, while Raju enters from the left of the frame, crouching toward Rita, and in his walk hiding the moon behind him, while the reflection gets blurred because of ripples occurring suddenly on the water surface. Chatterjee calls this technique a “common popular practice for a discreet reference to sexual union”.

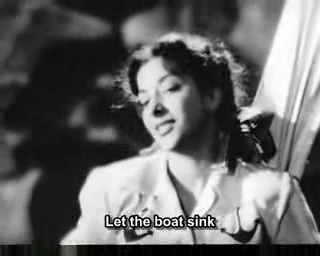

Pointing out the fact that this, however, is not the end of the sequence, and that the scene proceeds till Rita says to Raj “Let the boat sink!”, Chaterjee writes: “The final word comes from the woman, on the eve of her attaining the age of consent”.

She also points out that the maidenly shyness, coupled with the boldness of her initiative, may signify a certain amount of dignity in and sexual freedom of what she calls the ‘new woman in Indian cinema’. However,

− “The ‘dignity’ given to the new woman in the Indian cinema can be seen as a thin crust on a rotten cake; for, after all, she is only complying to the wishes of the man, while being subjected to the viewing pleasure of the audience.”

Although, it is the woman who is making the decision regarding her sexual freedom, not much is liberated, as she is still submissive and still very much a captive in the patriarchal Indian society.

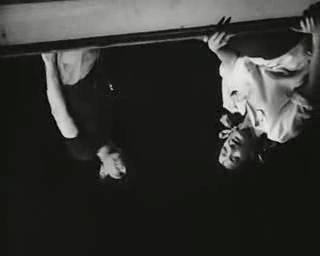

The treatment of sexual liberation of the woman in Indian cinema as shown in Guide (1965), contrasts with the depiction of the woman in Awara. The song and dance sequence “Aaj phir jeene ki tamanna hai” begins with a wide shot of the heroine, Rosie, played by Waheeda Rahman, and Raju, played by Dev Anand, on the back of a truck carrying hay. The camera dollies along following the couple, after she has just stolen an earthen pitcher from one of the village women. Then a panning shot, taken from the side of the truck, shows Rosie handing the earthen vessel to Raju while she starts singing:

− “kaanto se kheech ke yeh aanchal;

tod ke bandhan, baandhe paayal;

koi naa roko dil kee udaan ko, dil wo chalaa.”

Translation:“I have broken away from thorns/ I have broken bonds, and worn an anklet/ do not stop the flight my heart has taken, it is gone.”

The lyrics themselves highlight Rosie’s desire to break free from all the social restrictions that she has been forcefully subjected to. She is the daughter of a courtesan, who, not wanting her daughter to suffer the same fate as herself and be always looked at by the society with disdain, decides to her marry Rosie off to a much older, but socially respectable archaeologist. On her first night with her husband, Rosie finds out that he is sexually impotent, and incapable of either satisfying her sexually, or giving her a child. In fact, the first time her mother comes to visit them, Rosie cries on her shoulders and upon being asked, tells her that she could not have children because of her husband’s inability. This song is important in the development of the narrative as it shows Rosie letting go of her inhibitions completely. Not only does she want to experience a new sexuality, but also breaks away from her past and traditional rules of the society. The above quoted stanza is followed by a shot of Rosie throwing the earthen vessel on the road, where it shatters to pieces.

Sequence 3 from Guide(1965)

The shattering of the earthen vessel becomes symbolic of her deviation from the traditional ‘village’ values, towards a future of self-fulfillment. The sequence follows the couple to location at the ruins to Udaipur, where “Aaj phir jeene ki tamanna hai” assumes, not just a mere denial, but a blatant opposition to her on-screen husband, who is an archaeologist, and the social hierarchythat has forced the woman’s sexuality into pardah since the times these ruins represent. Shots of Rosie in natural light, wearing a simmering light blue sari, running around, hugging the ancient idols of gods, with the camera tracking in to frame close-ups of her uninhibited self, is representative of her liberation. However, there is still a sense of hesitation, where society is concerned. She sings:

− “dar hai safar mein kahee kho naa jaoon main;

ratsaa nayaa.”

Sequence 4 from Guide(1965)

The road of sexual independence is still quite new for her, and she perturbed for a brief moment regarding her acceptance in the society, even after her rejection of its values. She is also uncertain as to the consequence such decisions could have. The areal shot shows Rosie walking on the ledge, trying to not lose her balance and fall off, while the deep focus enables the viewer to look at Raju beyond her, standing below, quite anxiously waving at her and following her, ready to catch her if she fell.

This single shot constitutes the microcosm of the narrative regarding her taking a new and potentially dangerous path with the help of Raju, who is there to back her up if something goes amiss. And as the story unfolds, this is exactly what happens: Rosie leaves her husband and Raju supports her, and helps her rise to stardom. The following chorus echoes her resilience, willingness to assume the responsibility for her own actions: “Aaj phir jeene ki tamanna hai”.

For both Rita and Rosie, society becomes a concern, but not enough to prevent them from making their own decisions. While Rita, according to Chaterjee still remains submissive, because she is still complying with the man’s wishes, while proclaiming sexual independence, Rosie does not follow anyone except her own dictates; Rosie does not come on to Raju, like Rita, nor are there physical evidences of sexual undercurrents, except in a few close-ups showing the way Raju looks at Rosie. This proclamation of sexual sovereignty as a key theme in the two song and dance sequences detach the two women from the society. The couple is shown to be alone in both the sequences, signifying the on-screen removal or disavowal of society and its conventions, though in reality, it may not be so.

In later years, even love songs of courtship and display of sexual desires become choreographed with the participation of the extras, the professional dancers, which results in the loss of privacy, as well as portraying a certain acceptance shown by the diegetic society, represented by the extras. As Sudhir Kakkar writes:

− “Some may even consider such a thorough-going denial of external reality in Indian cinema to be a sign of morbidity, especially since one cannot make the argument that fantasy fulfills the need for escapism of those suffering from grinding poverty.”

Rosie’s song also makes use of that fantasy element in the creation of cinephilia. In the song we see an amalgamation of desire and fantasy, as a narrative device to portray Rosie’s sexual sovereignty. Kakkar earlier in his essay writes:

− “Fantasy is the mise-en-scène of desire, its dramatization in a visual form. The origins of fantasy lie in the unavoidable conflict between many of our desires, formulated as demands on our environment (especially on people), and the environment’s inability or unwillingness to fulfill our desires, where it does not proscribe them altogether. The power of fantasy, then, comes to our rescue by extending or withdrawing the desires beyond what is possible or reasonable, by remarking the past and inventing a future.”

The fact that society outside the theatre may not permit this sexual liberation of the woman, adds the fantasy to these song and dance sequences. The audience in the theatre revel in this projection of desire, as is evident by the success of these to films and especially the two songs. Rosie’s fantasies in the sequence comprise of the conflict between her desire to experience sexual satisfaction and to have children with her husband, and the fact that it cannot be so because of her husband’s shortcomings.

3. Voyeurism.

One of the most important techniques used in the depiction of women on screen is the use of camera as a voyeuristic device, to facilitate the creation of an objectified image of the female.

The song and dance sequences highlight this kind of use of camera, being seeped in the scopophilic narratives (Scopophilia is the ‘pleasure of looking’, as noted by Kasbekar), that use the female body and, at times specific female body parts, as an object of fetishism. Such a construction of a sequence, based of the voyeuristic gaze of the spectators, both raising and satiating the erotic “look” of the theatre audience is based wholly on the demands of the patriarchal consumer and consequently results in providing the film-maker with few other alternatives than to include one or two of such song and dance sequences, which in our time have come to be called ‘item numbers’, if they want to make a commercially successful film.

The pleasures of scopophilia, are the foundation on which this objectified construction of a woman is based. As Kasbekar notes about the scopophilic function of the woman in Hindi cinema:

− “Central to the pleasures of heterosexual scopophilia, is the role of the woman, and, as in Hollywood films, in Hindi cinema too she functions primarily to address the erotic gaze and constitutes an indispensable ingredient in look-soliciting strategies.”

In the song “Tujhe bulayen yeh meri baahein” , in the film Ram Teri Ganga Maili, the heroine, Ganga, played by Mandakini, the wet, white sari, clinging to the woman’s body, leaving barely anything to imagination, epitomizes the demise of social censors. One sequence within the song shows, in extra wide shot, Ganga, dancing under a waterfall, wearing a see-through, wet sari, singing to skies, completely unaware of the voyeur hero, Narendra, played by Rajiv Kapoor, who is watching her.

At one level, the sequence is a comment on the voyeuristic tendencies of not just the hero, but also the spectators, as well, who are feasting their eyes on her body, every time there is a cut to close-up of particular parts of her body, like breasts, hips and legs. Steve Derné and Lisa Jadwin, in their essay, note how the film, although regularly criticized by “both media and common people for having exposed the breasts of the heroine” was enjoyed by many film goers.

Therefore, the exposing of the body parts of Ganga become prime examples of the fetishism that is employed in inciting and satiating the voyeuristic gaze of the audience. An example of such a technique in the song takes place when midway through the waterfall dance sequence, a low-angle shot focuses on Ganga’s legs and hips from behind her, and pans right to include a long shot of her in the centre of the frame as she walks from the left to right of the frame.

Sequence 5 from Ram Teri Ganga Maili(1985)

Kasbekar points out:

− “The use of bogus ethnic costumes (scanty ‘tribal’ costumes, ‘African grass’ skirts) or of the ‘wet sari’ (occasioned by a sudden downpour during the song) that draws the viewers’ attention to overinflated bosoms, allow for as ample a display of the female body as can be achieved, without inviting the displeasure of the nation’s moral police.”

Ganga is an innocent village girl, whose sexual awareness is brought about only after her interactions with Narendra. As such, she has no qualms about dancing semi-nude under the waterfall. Referring to Ganga’s downfall from purity, Kasbekar cites it as a “metaphor for the overall moral collapse of India”.

The diegetic voyeur, here Narendra, acts as the representative of the Indian audience, amalgamating the spectator’s voyeuristic gaze, with that of his own, looking at the spectacle, the fragmented body parts of Ganga, rendering the diegetic spectator as the voyeur, while granting the theatre audience permission to do the same, without any feeling of guilt.

Kasbekar further writes with regards to this phenomenon:

− “Consequently,the charge of voyeurism is displaced on to the (often leering) diegetic spectator, establishing him as the holder of the erotic gaze instead of the actual spectator watching the film in a cinema.”

However, in the sequence, Narendra can only see her from a distance; he does not the ‘privilege’ to examine specific parts of her body, with the help of close-ups and the use of the camera as a voyeuristic device, like the audience does. Therefore, although he establishes himself as the voyeur and “disavows any voyeuristic intent on the part of the spectators in the cinema”, in the limitation of his visual accessibility lies his detachment from the voyeuristic guilt.

4. Conclusion:

The three women mentioned above have been taken from separate decades, the diegetic treatment of each, symbolizing the progressing stages in the transition of the heroine in Hindi Cinema from a mythical ‘ideal’, to a more sexually aware and sovereign character, who is not afraid to go against the social norms. For example, Rita’s decision to “Let the boat sink!”, despite all her reservations with regards to her profession as a lawyer, or her position in the society, draws a parallel with Rosie’s decision to leave her husband, even though she is the daughter of a courtesan and has nowhere to go except with a guide she meets in Udaipur. Similarly, Ganga’s decision to let Narendra make love to her, have his child, and then take the child back to Narendra, even after she finds out that he is engaged to someone else, and in the process going through one ordeal after another, is representative of a new boldness that was very new to Hindi cinema. The ideal woman no longer remains the demure, docile, virtuous, virgin but comes to be characterized by a newly acquired awareness of her sexuality, one who is bold enough to oppose the society and its patriarchal conventions in pursuit of what she believes to be rightful. As the costumes, saris, other apparel of the heroine became increasingly revealing and erotic, the debates regarding the suitability of western influences were brought to the surface. These debates regarding the demise of traditional values and morality because of such influences still remain active and unresolved, and beyond the scope of this essay. However, the aim of this essay is to observe and examine the change as seen represented through one song and dance sequence from each decade that portrays this change. And as seen above, the transformation that took over three decades, resulted in the complete breakdown of at least one convention, that the ideal woman is not supposed to display her sexuality or sexual freedom.

References:

Bagchi, A. (1996). “Women in Indian Cinema”. http://www.cs.jhu.edu/~bagchi/women.html. Accessed on February 24th, 2008.

Chatterjee, G. (2003). “Awāra”. New Delhi: Penguin Books India (P) Ltd.

Derné, S. and Jadwin, L. (2000). “Male Hindi Filmgoer’s Gaze: An Ethnographic Interpretation of Gender Construction”. Contributions to Indian Sociology, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 243-269.

Gopalan, L. (2003). “Cinema of Interruptions: Action Genres in Contemporary Indian Cinema”. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Kakkar, S. (2007). “Lovers in the Dark” in “Indian Identity”. New Delhi: Penguin Books India (P) Ltd.

Kasbekar, A. (2007). “Hidden Pleasures: Negotiating the Myth of the Female Ideal in Popular Hindi Cinema” in “Pleasure and the Nation: The History, Politics and Consumption of Public Culture in India”. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Thoraval, Y. (2000). “The Cinemas of India”. New Delhi: Macmillan India Ltd.