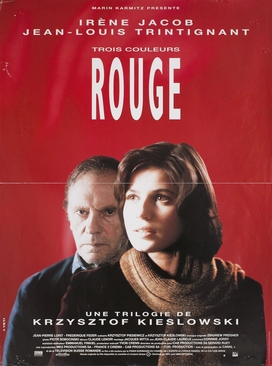

The grand and majestic conclusion the Three Colours Trilogy, Red takes loosely connected lives and creates a masterful web of rich and complex philosophical narrative of loss, fraternity, and perhaps redeeming love.

Three Colours: Red is the final entry in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Three Colours trilogy, a triumphant conclusion where the lives of the three sets of characters in the trilogy finally converge. The trilogy is named after the three colours of the French national flag, and is based on the French Revolutionary ideals of liberty (Three Colours: Blue), equality (Three Colours: White), and fraternity (Three Colours: Red). This would also be the great Polish filmmaker’s last work.

Themed on fraternity, Red examines the interconnectedness of human lives, intertwined in ways that may not always be apparent, the invisible bonds that bind us. The opening sequence itself summarizes the core ideology behind the film: someone punches a phone number into a keypad, in Geneva (where the film is set); the camera then races along an invisible network of wires, through several switches, along an undersea cable, and re-emerging in England, following the path of the electronic code through a network of optical fibres. Jonathan Dawson writes:

[…] Now we hear a mounting babble of voices gather and mix as the cables dive into the water, rush along the seabed to emerge and whiz through subterranean tunnels until… we hear an engaged signal!

Bad luck or bad timing?[…]

Seemingly loose elements in the film’s narrative all come together as the story progresses. Valentine (Irène Jacob) is a student in Geneva and a struggling, part-time model, who is modeling for a bubblegum promo. She is in love with an emotionally distant man named Michael, who lives in England, and is constantly suspicious of her. His insecurity leads him to such a stage where tries to control all her actions, including telling her when to go to sleep. A young law student, Auguste (Jean-Pierre Lorit), who lives across the street from Valentine and is studying to be a judge, is in love with a woman named Karin who provides personalized weather forecasts to travelers.

Throughout the film, Valentine and Auguste rub shoulders but never meet, in a string of missed opportunities, until at the very end, when all the pieces fit together. Because of a dog she ran over, she meets a retired judge called Joseph (Jean-Louis Trintignant), who, she later finds, spies on his neighbours’ phone calls, not for money but to feed his own cynicism regarding the outside world, based on a past betrayal.

[…] That’s the set up for Red but from these crisp snapshots emerges a rich and complex philosophical narrative of loss and, perhaps, by the end, redeeming love. […]

The accident sparks off a chain of events beginning with the meeting between Valentine and Joseph, to the meeting between Auguste and Valentine during a disaster at sea. Through many twists and turns, the unpredictable plot takes the viewer on a journey through the lives of a few people, and in the end (following the theme of fraternity) alleviation of loneliness and a hopeful redemption of love.

As with the preceding films (Blue and White), the dominance of the title colour (in this case Red) is apparent throughout the film. But in Red the use of this colour metaphor is reminiscent of Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers (1972). According to Roland Barthes, Red is a

[…] universal linguistic signifier of love and blood, life and death […]

Jonathan Dawson adds:

If the colour (bright) red is set to stand for both danger and the possibility of passion when all else has withered, the confrontation between Valentine and the judge is also the isotopic centre of the film. The clash between experience and disappointment, youth and the potential for the inevitable suffering, that makes us fully human, is yet to come.

The poster resulting from Valentine’s bubblegum photoshoot, where her face is repeatedly photographed against the backdrop of a red cloth appears at various moments in the film: the most important image being towards the very end of the film. Anthony Leong observes:

[…] Valentine’s picture for the chewing gum ad is exactly the same as the final image of the newscast after she has met Auguste and been rescued from the ferry sinking; however, the context is different in each image. […]

Coincidence also adds to the connections: while Auguste is crossing the street one night, the elastic holding his books together snaps, and the books fall onto the street. One book falls open on a certain page, which he reads, and his subsequent exam asks a question relevant to that material. Thirty-five years earlier, the same thing happened to the older judge, while he was in a theatre.

One metaphor that Kieslowski deploys in this film, that he did not use in his previous films in the trilogy is the use of wires/ telephone and windows to portray some kind of emotional detachment of the film’s characters with the events happening around them. Joseph sees the world outside through a window; Auguste sees his girlfriend betray him through a window etc.

For the character of Joseph, the windows represent the cynicism he feels and the emotional detachment he has from the world outside as a result of his betrayal in the past. The window is a physical barrier that separates him from the harsh environment and prevents him from interacting with it, yet he can see what is going on.

And the same metaphor is continued when Joseph starts opening up to world outside, and the neighbours throw stones at his windows shattering them.

What leaves a lasting impression on the viewer is, despite all the interpretation, and the metaphors, and the imagery, and the narrative subtexts that this film might have, the simplicity of the scene where the old judge muses to Valentine:

“Perhaps you’re the woman I never met!”

Telephones become prisons, allowing relationships to exist and transcend distances, yet unable to make the relationships that result from them, sustainable. For Kieslowski, relationships that arise from an artificial connection, such as telephone lines, will fail. Only the relationships with a basis in the physical or metaphysical world survive.

It is also of note that while in the other two films of the trilogy, the protagonists (Julie in Blue and Karol in White), became isolated because of the hollowness of their goals, liberty and equality respectively, fraternity in fact has a positive result on its characters. Thus, it is not just because of the warmth of the colour Red, but also because of Kieslowski’s treatment of the matter, that Red is considered to be the ‘warmest’ of his films. It is ‘Love’ that enables Julie to embrace the world she has tried to shut out; Karol and Dominique realize they still love each other and are able to start their life afresh; it is the old judge’s affection towards Valentine that allows him interact with the outside world.

If White was suffused with a sense of play and Blue a cool meditation on awful and bottomless loss, where the unfinished music of the orchestral work for “a new Europe” served as a character as much as any of the actors, Red brings the themes together with a meditation on the nature of brotherhood and, yes, humanity itself.

And yet Valentine does not start out being benevolent for the sake of brotherhood or fraternity:

-Why did you pick up Rita?

-Because I’d run her over. She was bleeding.

-Otherwise you’d have felt guilty. You’d have dreamt of a dog with a crushed skull.

-Yes.

-So who did you do it for?

But it is love that according to Leong

[…] saves all the principals of the trilogy from the trials and tribulations which they face, which is fitting considering the theme of “Red”[…]

Throughout the film Valentine plans to go see Michael in England, but Joseph convinces her to take the ferry across the Channel instead of flying. She agrees. And in the last scene of the film (one could say the Trilogy), a storm that had been building throughout the film sweeps into the Channel sinking the boats. There are only 7 survivors: Julie and Olivier from Blue, Karol and Dominique from White, Valentine and Auguste, who meet for the first time, as well as an English bartender named Stephen Killian. The film’s final image reproduces the poster image of Valentine.

Quoting Dawson again:

[…] [the storm] in the much debated (and often decried) climacteric, unites the key characters from Blue, White and Red in an astonishingly daring piece of narrative rule-breaking. It is a climax, however, that makes absolute emotional sense in the light of Kieslowski’s obsessions with chance, luck and destiny […]

A true masterpiece of cinema, Kieslowski’s best work, a majestic end to the trilogy, and the filmmaker’s career, Three Colours: Red won the Best Foreign Language Film award at Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards, National Society of Film Critics Awards, New York Film Critics Circle Awards, National Board of Review. It also won the Cesar Award for Best Music, and many others.

Shortly after finishing this film (and the trilogy), Kieslowski had a heart surgery, from which he never woke up.